December Worship theme:

Stillness

Stillness

December 27 Sunday Service:

2020: Goodbye and Good Riddance

Sermon by Rev. Beth Miller

I don’t have to tell you what a strange and painful year this has been. We know. We remember. We grieve. We say “goodbye, we’re glad you’re finally over.” In addition to the sermon, we will acknowledge the losses we grieve and spend some time in a ritual of letting go of what we’re glad to be rid of. If you were able to come to the Christmas Eve Wassail Drive Through, bring the little slip of paper that was in your gift bag, a pen, and a small bowl of water with you to the service. If not, any slip of paper will do.

2020: Goodbye and Good Riddance

Sermon by Rev. Beth Miller

I don’t have to tell you what a strange and painful year this has been. We know. We remember. We grieve. We say “goodbye, we’re glad you’re finally over.” In addition to the sermon, we will acknowledge the losses we grieve and spend some time in a ritual of letting go of what we’re glad to be rid of. If you were able to come to the Christmas Eve Wassail Drive Through, bring the little slip of paper that was in your gift bag, a pen, and a small bowl of water with you to the service. If not, any slip of paper will do.

December 20 Sunday Service:

The Day the Sun Disappeared

Sermon by Rev. Budd Friend-Jones

As Earth tilts away from the sun on its spatial journey, Winter Solstice (December 21) marks the longest night and shortest day of our year. Cultures on this circling sphere find many meanings in this celestial phenomenon. They’ve invented festive rituals to “bring back the sun”. We’ll consider a strangely delightful story from Japan as we celebrate the Solstice in the midst of our own long night in a troubled world.

The Day the Sun Disappeared

Sermon by Rev. Budd Friend-Jones

As Earth tilts away from the sun on its spatial journey, Winter Solstice (December 21) marks the longest night and shortest day of our year. Cultures on this circling sphere find many meanings in this celestial phenomenon. They’ve invented festive rituals to “bring back the sun”. We’ll consider a strangely delightful story from Japan as we celebrate the Solstice in the midst of our own long night in a troubled world.

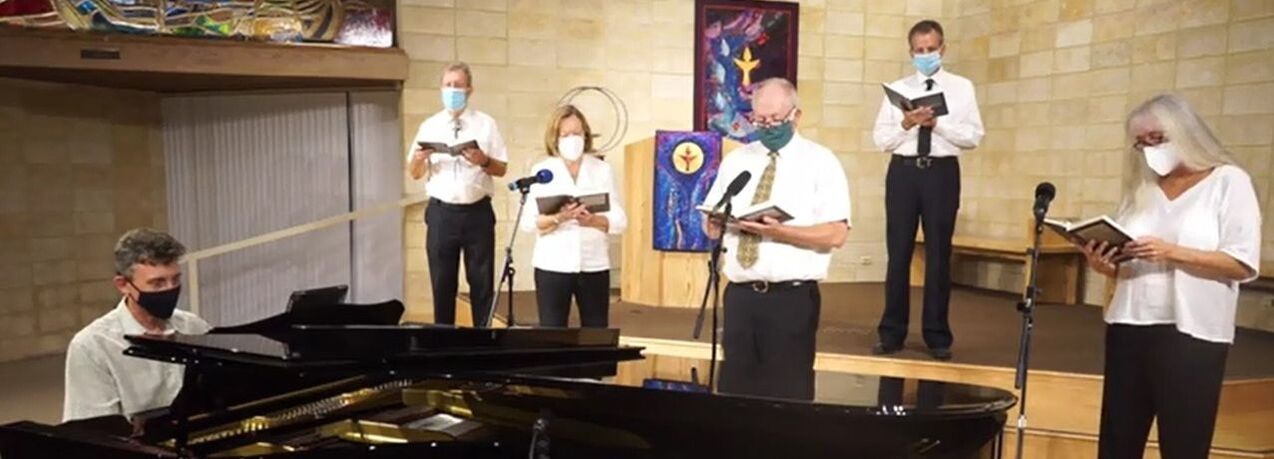

Music for these recordings has been provided by Don Bryn, Robert Lischetti and the "Masked Mini-Choir"

December 13 Sunday Service:

Whom Do We Serve and

Who Is My Neighbor?

Sermon by Rev. Doug Wadkins

This service will explore the implications of the second set of missional identity questions to be explored by the congregation. These questions seek to illuminate the truths of our context and how that might impact our sense of purpose for the future. Also in the service, a special meditation for the season of Hanukkah.

"Whom Do We Serve?" conversation after Coffee Hour at 1 pm, as noted below.

Whom Do We Serve and

Who Is My Neighbor?

Sermon by Rev. Doug Wadkins

This service will explore the implications of the second set of missional identity questions to be explored by the congregation. These questions seek to illuminate the truths of our context and how that might impact our sense of purpose for the future. Also in the service, a special meditation for the season of Hanukkah.

"Whom Do We Serve?" conversation after Coffee Hour at 1 pm, as noted below.

December 6 Sunday Service:

Find a Stillness

Sermon by Rev. Doug Wadkins

December can be a very busy month and yet much of its deeper truths come forward when we slow down. It is also likely that the ongoing pandemic may ask for us to be very careful about gathering and so what might be made more meaningful about this time at home? This service will explore the power and meaning of “stillness” for this season.

Find a Stillness

Sermon by Rev. Doug Wadkins

December can be a very busy month and yet much of its deeper truths come forward when we slow down. It is also likely that the ongoing pandemic may ask for us to be very careful about gathering and so what might be made more meaningful about this time at home? This service will explore the power and meaning of “stillness” for this season.

For subtitles, click the red "play" button, then click the CC button in the bottom right corner.

Having trouble viewing this? Click the red "play" button, then click the gear icon in the bottom right corner and change quality to a smaller number. For large screens, use a larger number. Read more...

Having trouble viewing this? Click the red "play" button, then click the gear icon in the bottom right corner and change quality to a smaller number. For large screens, use a larger number. Read more...

Rev. Brock Leach

Rev. Brock Leach

November 29 Sunday Service:

Building a Multicultural Movement

Sermon by Rev. Brock Leach

In this moment of overwhelming divisiveness, it’s hard to imagine how we might cross cultural boundaries to tackle our common human challenges. As part of my UUA work supporting religious innovators, I’ve been interviewing ministers of culturally diverse congregations to learn what they know about building and sustaining multicultural communities. Their answers are hopeful and inspire me to imagine how Unitarian Universalism can show the way forward.

Rev. Brock Leach is one of our local community ministers. As Vice-Chair of the Unitarian Universalist Service Committe (UUSC), he is working to advance social justice and social entrepreneurship. He currently serves as an executive consultant to the UUA for its Innovative Ministries project and has helped develop and lead its Entrepreneurial Ministry program in partnership with the UU Ministers Association. Prior to that, Leach was vice-president of mission, strategy and innovation at UUSC where he helped create and launch the UU College of Social Justice; Commit2Respond, a UU-wide campaign for Climate Justice; and UUSC’s Justice-Building Program.

Building a Multicultural Movement

Sermon by Rev. Brock Leach

In this moment of overwhelming divisiveness, it’s hard to imagine how we might cross cultural boundaries to tackle our common human challenges. As part of my UUA work supporting religious innovators, I’ve been interviewing ministers of culturally diverse congregations to learn what they know about building and sustaining multicultural communities. Their answers are hopeful and inspire me to imagine how Unitarian Universalism can show the way forward.

Rev. Brock Leach is one of our local community ministers. As Vice-Chair of the Unitarian Universalist Service Committe (UUSC), he is working to advance social justice and social entrepreneurship. He currently serves as an executive consultant to the UUA for its Innovative Ministries project and has helped develop and lead its Entrepreneurial Ministry program in partnership with the UU Ministers Association. Prior to that, Leach was vice-president of mission, strategy and innovation at UUSC where he helped create and launch the UU College of Social Justice; Commit2Respond, a UU-wide campaign for Climate Justice; and UUSC’s Justice-Building Program.

November 22 Sunday Service:

Things to Make the Season Bright

Sermon by Rev. Douglas Wadkins

As we move into another holiday season, beginning with Thanksgiving, there are often a variety of experiences of the time. Even in typical years, it is often a time of challenge as well as opportunity. We know that this season is likely to be even more of a challenge and so we will explore ways to journey through the coming weeks with greater intention, meaning, and compassion.

Things to Make the Season Bright

Sermon by Rev. Douglas Wadkins

As we move into another holiday season, beginning with Thanksgiving, there are often a variety of experiences of the time. Even in typical years, it is often a time of challenge as well as opportunity. We know that this season is likely to be even more of a challenge and so we will explore ways to journey through the coming weeks with greater intention, meaning, and compassion.

Click here for the Stories of Hope, referred to in Doug's sermon.

November 15 Sunday Service:

Your Five Shining Stars

Sermon by Rev. Douglas Wadkins

Over the past months, I have been working diligently to listen to what you have told me about the strength and heart of the congregation. This service will synthesize what I have heard and share with you the Five Shining Stars that help you successfully navigate the sometimes soothing, sometimes challenging, and often stormy seas of life. The five shining stars are five major sources of wisdom, courage, and inspiration for this specific congregation that you have told me are important. With each, I will explore the strengths and challenges they offer.

Your Five Shining Stars

Sermon by Rev. Douglas Wadkins

Over the past months, I have been working diligently to listen to what you have told me about the strength and heart of the congregation. This service will synthesize what I have heard and share with you the Five Shining Stars that help you successfully navigate the sometimes soothing, sometimes challenging, and often stormy seas of life. The five shining stars are five major sources of wisdom, courage, and inspiration for this specific congregation that you have told me are important. With each, I will explore the strengths and challenges they offer.

November 8 Sunday Service:

Where Do We Go

from Here?

Sermon by Rev. Douglas Wadkins

Even if we do know the final election results as we gather for worship this weekend, there is so much mystery, angst, and hurt to sort through in the coming time. Perhaps this sermon might be more accurately understood as an exploration of how we might best journey forth from this point. Join us to explore how we might think about the work ahead and what resources will best aid us in finding the strength, courage, and compassion to get there.

Where Do We Go

from Here?

Sermon by Rev. Douglas Wadkins

Even if we do know the final election results as we gather for worship this weekend, there is so much mystery, angst, and hurt to sort through in the coming time. Perhaps this sermon might be more accurately understood as an exploration of how we might best journey forth from this point. Join us to explore how we might think about the work ahead and what resources will best aid us in finding the strength, courage, and compassion to get there.

November 1 Sunday Service:

What the Pilgrims Didn’t Hear:

The Silence of Massasoit

Sermon by Rev. Budd Friend-Jones

400 years ago, the Mayflower dropped anchor off Cape Cod beginning a new chapter in North American history. In 1970, Wampanoag native Frank B. James was invited to give a commemorative oration to celebrate the anniversary on behalf of indigenous Americans. He would have recommended that Thanksgiving Day become a day of new beginnings in the relationships between our peoples. Instead, his speech was suppressed. Can we recover his vision?

Pictured above is a painting of Massasoit wearing the red horseman's coat that he was given as a gift in the spring of 1621 by Edward Winslow and Stephen Hopkins on behalf of the Plymouth colonists. Painting courtesy of Ruth DeWilde-Major.

What the Pilgrims Didn’t Hear:

The Silence of Massasoit

Sermon by Rev. Budd Friend-Jones

400 years ago, the Mayflower dropped anchor off Cape Cod beginning a new chapter in North American history. In 1970, Wampanoag native Frank B. James was invited to give a commemorative oration to celebrate the anniversary on behalf of indigenous Americans. He would have recommended that Thanksgiving Day become a day of new beginnings in the relationships between our peoples. Instead, his speech was suppressed. Can we recover his vision?

Pictured above is a painting of Massasoit wearing the red horseman's coat that he was given as a gift in the spring of 1621 by Edward Winslow and Stephen Hopkins on behalf of the Plymouth colonists. Painting courtesy of Ruth DeWilde-Major.

With the election just over a week away you've already decided how you will vote, and have likely done so already. This is not about voting. It's about the separation of church and state, the rules governing religion and politics, and Unitarian Universalism’s long history of social and political involvement. Regardless of Tuesday’s outcome, such involvement will still be crucial in the weeks and months ahead.

October 18 Sunday service:

Holy Conversations in Times of Change

Sermon by Rev. Doug Wadkins

We talk to our friends, family, and coworkers often, but there are ways in which this can be understood as something that takes us to a much deeper level of understanding. In this service we explore what makes a conversation holy.

Sermon by Rev. Doug Wadkins

We talk to our friends, family, and coworkers often, but there are ways in which this can be understood as something that takes us to a much deeper level of understanding. In this service we explore what makes a conversation holy.

October 4 Sunday service

Animal Blessing

With Rev. Doug Wadkins, Rev. Beth Miller and Rev. Budd Friend-Jones officiating

This service will honor and bless the creatures in our lives that offer us love and connection. The service will also include a time of remembering beloved animals that have passed from our lives. We will invite you to send in pictures of pets in preparation for the service. This is a prerecorded service, available anytime as usual, but because it is an Animal Blessing with a ritual at the live coffee hour at 11:30 we suggest people watch it at 10:45 or earlier and then participate in the ritual

Animal Blessing

With Rev. Doug Wadkins, Rev. Beth Miller and Rev. Budd Friend-Jones officiating

This service will honor and bless the creatures in our lives that offer us love and connection. The service will also include a time of remembering beloved animals that have passed from our lives. We will invite you to send in pictures of pets in preparation for the service. This is a prerecorded service, available anytime as usual, but because it is an Animal Blessing with a ritual at the live coffee hour at 11:30 we suggest people watch it at 10:45 or earlier and then participate in the ritual

September 27 Sunday service

The Oasis

Sermon by Rev. Doug Wadkins

As we move into an autumn unlike any other for so many reasons, we are likely feeling a range of things including some sense of being anxious and perhaps even a bit heavy of heart. This service will explore some of the practices that recharge and connect us especially in times of great change or stress.

The Oasis

Sermon by Rev. Doug Wadkins

As we move into an autumn unlike any other for so many reasons, we are likely feeling a range of things including some sense of being anxious and perhaps even a bit heavy of heart. This service will explore some of the practices that recharge and connect us especially in times of great change or stress.

September 20 Sunday service:

A New Year Awaits

Sermon by Rev. Doug Wadkins

The High Holy Days are an invitation to renewing our sense of purpose, rethinking our important relationships, saying goodbye to that which does not serve us, and committing to new, life-giving practices.

A New Year Awaits

Sermon by Rev. Doug Wadkins

The High Holy Days are an invitation to renewing our sense of purpose, rethinking our important relationships, saying goodbye to that which does not serve us, and committing to new, life-giving practices.

September 13 Sunday service

Renewing Our Sense of Purpose

Sermon by Rev. Doug Wadkins

We have recently explored the importance of self-knowledge in other services, and this knowledge may be put to good work and thinking about meaning and purpose and life. This service will explore the vital practice for any age and stage in life of one’s vocation. In turn, this renewed sense of individual purpose can create new energy and possibility for the larger community.

Renewing Our Sense of Purpose

Sermon by Rev. Doug Wadkins

We have recently explored the importance of self-knowledge in other services, and this knowledge may be put to good work and thinking about meaning and purpose and life. This service will explore the vital practice for any age and stage in life of one’s vocation. In turn, this renewed sense of individual purpose can create new energy and possibility for the larger community.

September 6 Sunday service

Visible Heroes Facing Invisible Threats

Sermon by Rev. Beth Miller, Associate Minister

The pandemic has given us a new awareness of what is essential to maintaining the smooth operation of society and who the people providing those services are. It has also made us painfully aware of how undervalued many of those people are. On this Labor Day Sunday, when picnics and street fairs are far less attractive to most of us, let us celebrate the worth and dignity of work. And let’s think about how we can improve the lives of those whose work is essential.

Click anywhere on the video to play.

Visible Heroes Facing Invisible Threats

Sermon by Rev. Beth Miller, Associate Minister

The pandemic has given us a new awareness of what is essential to maintaining the smooth operation of society and who the people providing those services are. It has also made us painfully aware of how undervalued many of those people are. On this Labor Day Sunday, when picnics and street fairs are far less attractive to most of us, let us celebrate the worth and dignity of work. And let’s think about how we can improve the lives of those whose work is essential.

Click anywhere on the video to play.

August 30 Sunday service

Know Thyself

Sermon by Rev. Douglas Wadkins

One of the oldest philosophical pursuits is exploring the inner self and its relationship to the outer world. All we can know and indeed all that we do is inspired by, interpreted through the truth of who we truly are. Gaining that knowledge is harder than it sounds. This service will explore the pathway and importance of the practice of knowing ourselves. (See video on homepage.)

Know Thyself

Sermon by Rev. Douglas Wadkins

One of the oldest philosophical pursuits is exploring the inner self and its relationship to the outer world. All we can know and indeed all that we do is inspired by, interpreted through the truth of who we truly are. Gaining that knowledge is harder than it sounds. This service will explore the pathway and importance of the practice of knowing ourselves. (See video on homepage.)

August 23 Sunday service

The Art of Friendship and the Pandemic

Sermon by Rev. Douglas Wadkins

As we begin another cycle of the year within the life of the congregation, this service focuses on the particular importance of understanding friendship as a spiritual practice, especially in this time of increased isolation. We will explore why friendship matters so much now, and how to best understand its power in our lives..

The Art of Friendship and the Pandemic

Sermon by Rev. Douglas Wadkins

As we begin another cycle of the year within the life of the congregation, this service focuses on the particular importance of understanding friendship as a spiritual practice, especially in this time of increased isolation. We will explore why friendship matters so much now, and how to best understand its power in our lives..

August 9 service:

The Power and Possibility of Change

Reflections by the Revs. Doug Wadkins, Beth Miller and Budd Friend-Jones

As we begin this interim time of transition, let us reflect on changes in our own lives, changes in this congregation, and changes in the ways that the world has been transformed. All of this will help us think about meaningful answer to the question, “what is the world asking of me and of us in the next few years?”

The Power and Possibility of Change

Reflections by the Revs. Doug Wadkins, Beth Miller and Budd Friend-Jones

As we begin this interim time of transition, let us reflect on changes in our own lives, changes in this congregation, and changes in the ways that the world has been transformed. All of this will help us think about meaningful answer to the question, “what is the world asking of me and of us in the next few years?”

AUDACIOUS ICONS AND THE SOUL OF AMERICA

Sermon by Budd Friend-Jones

August 2, 2020

This morning I want us to remember and honor three great individuals in our nation’s recent history. To paraphrase the Herald-Tribune, they were among the Founding Fathers and Founding Mothers of a Better America. They invested their lives in overcoming racism and other oppressions in America. All three were ordained ministers. All three worked at the center of the Civil Rights Movement from the 1950’s down to the present time. All three received our nation’s highest honor, the national Medal of Freedom.

On March 27, the Reverend Joseph Echols Lowery passed away at age 98. He was followed in death by the Reverend C. T. Vivian on July 17, and by Congressman John Lewis the very next day.

Joseph Lowery is often called the Dean of the Civil Rights movement. He founded the Southern Christian Leadership Conference with Martin Luther King Jr. He helped lead the Montgomery bus boycott and headed the Alabama Civic Affairs Association, an organization devoted to the desegregation of buses and public places. He was a co-founder and president of the Black Leadership.

He protested the existence of Apartheid in South Africa and was one of the first five black men arrest outside the South African embassy in Washington, DC. He was a strong advocate for LGBTQ rights, including equality in marriage.

C. T. Vivian helped to organize the first sit-ins in Nashville in 1960 and the first civil rights march in 1961. He participated in Freedom Rides. He worked alongside Martin Luther King Jr. as the national director of affiliates for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. He led sit-ins at lunch counters, boycotts of businesses, and marches that continued for weeks or months in segregated cities. He was arrested often, jailed and beaten. At the end of a violence-plagued interracial Freedom Ride to Jackson, he was dispatched to the Hinds County Prison Farm, where he was beaten by guards. In 1964, he was nearly killed in St. Augustine, Florida, and once, on an Atlantic beach, roving white gangs whipped Black bathers with chains and almost drowned C.T. Vivian. Yet he always kept the focus of the struggle in a moral and spiritual context. He later wrote, “It was on this plane that the movement first confronted the conscience of the nation.” Fellow civil rights activists knew him as the “resident theologian” in King’s inner circle, Rev. Jesse Jackson recalled.

Until his death he was a fervent believer in Non-violence. He always instructed protesters, “Nonviolence is the only honorable way of dealing with social change, because if we are wrong, nobody gets hurt but us.”

And finally, of course, there is John Robert Lewis. So much has been said about him in the last few days, and deservedly so, but I hesitate to another word. From the days of his youth he was involved in peaceful protest and civil rights. He was one of the first Freedom Riders, beaten nearly to death, an organizer and speaker at the March on Washington, an organizer of the Selma to Montgomery march, and so much more. The son of sharecroppers in Alabama, he rose to the heights of power as a member of the US House of Representatives for 33 years. He has been called an “arc-bender”. He believed that the learning that matters most involves moral edification. History will remember him as one of the most respected moral and political leaders in our history.

All three have been called “Icons” of the Civil Rights Movement. I believe they were icons of something even larger. An Icon, in the classical religious sense, is a window into a higher realm.

These men, along with many others, were windows into the very best of human nature. In them we see integrity, courage, selflessness and a higher moral purpose. Through them we can glimpse what we also can be.

All three were co-workers with the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. All three were deeply immersed in the ethical and spiritual teachings of Jesus of Nazareth from the time they were children. All three also learned and practiced the spiritual disciplines of satyagraha and non-violence as articulated by Mohandas Gandhi and taught by James Lawson and re-enforced by Dr. King.

Satyagraha means “truth force”. It is the power that comes from living and acting in the Truth. It is the power of absolute integrity.

Non-violence is a way of life based on a profound love ethic, a love toward the other, no matter how egregious or hurtful their behavior is toward us.

Satyagraha leads toward greater justice. Non-violence leads toward the Beloved Community. These men never abandoned this philosophy.

For example, in the following clip, C. T. Vivian is speaking about the bombing of the Black church in Birmingham, Alabama, and the deaths of four little girls who were killed when the bomb detonated.

Watch C. T. Vivian on Bombing of Birmingham Church

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Rea1ftD5ePU

(Begin at 2:09 minutes in)

The true genius of the civil rights movement was its spiritual intentionality and inclusivity. It was never the Black race against the White race. As Vivian said, “What more can we do in freeing up not only African Americans but of (all) people in this nation? It’s not only a matter of freeing Black people, but of freeing White people as well. We really can’t free one without freeing the other.” He knew that we are all bound together as Dr. King said, in an “inescapable web of mutuality.” No one can truly be free from oppression until all of us are free together.

All of them knew they were involved in a great spiritual struggle. In 2004, John Lewis explained to PBS: “In my estimation, the civil rights movement was a religious phenomenon. When we’d go out to sit in or go out to march, I felt, and I really believe, there was a force in front of us and a force behind us, ’cause sometimes you didn’t know what to do. You didn’t know what to say, you didn’t know how you were going to make it through the day or through the night. But somehow and some way, you believed – you had faith – that it all was going to be all right.”

Watch John Lewis at Selma

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vumOmpv-L6A

Lewis constantly reminded us of the work still to be done to “redeem the soul of America”. “Don’t get lost in a sea of despair….,” he cautioned at the Edmund Pettis Bridge, and who should know better about that? Echoing both Vivian and King, he proclaimed, “We are one family, the human family. We all live in the same house, the American house…”

America is at a moral as well as a political and constitutional tipping point.

Black Lives Matter, said Melina Abdullah, its co-founder in Las Angeles, is much more than a movement for racial and social justice movement. At its core, she said, it is a spiritual movement.

Historian John Meacham has consistently observed that our present crisis is about the theology of America. Are we devoted to the words, “Thou shalt love thy neighbor as thyself”? Or are we devoted to the selfish pursuit of our own happiness, others be damned? The struggle is about the content of our character.

Watch Civil Rights Leader Rev. Joseph Lowery: 'We Ain't Going Back'

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TuPu5-cnF2Q

Let us rise up from the basement of race and color. Let us rise to the higher ground of the content of character….

The higher ground of character…

“Well, we ain’t goin’ back. We ain’t goin’ back. We’ve come to far, marched too long, prayed too hard, wept too bitterly, bled too profusely, and died too young to let anybody turn back the clock on our journey to justice.”

Let all the people say, Amen!

Reading “If we must die” by Claude McKay

During the summer of 1919, our country was struggling with two watershed moments. For a year-and-a-half the world had been engulfed by a devastating pandemic called the “Spanish Flu”; it would continue to infect communities for another year. In addition, the so-called Great War had just ended. Over five million soldiers were returning from abroad. They were seeking jobs that did not exist.

380,000 of those were African American. They too had borne the sacrifices of warfare for their country. They too expected its rights and benefits. W. E. B. Dubois, among others, urged them to continue their fight for democracy at home. But sadly, there were lynchings, church burnings and rampant anti-Black violence across the country.

This became known as “Red Summer”. Historians estimate that a thousand or more African Americans were killed before the violence subsided. Our country was caught in the clash of hope and threat, Time Magazine reported, between new dreams and entangled fears. This is the context for the poem you’re about to hear.

“If we must die” was written by Claude McKay, a central figure of the Harlem Renaissance. Jamaica-born, McKay was a novelist and poet of African descent. He blended his African pride with his love for British poetry. This is one of his most famous poems. He wrote it in the form of a Shakespearean sonnet. It speaks to the desperation felt among African Americans everywhere during “Red Summer”.

C. T. Vivian of blessed memory is the reader here. He was one of the primary architects of the non-violent civil rights movement that also gave us Dr. King, John Lewis, Joseph Lowery, James Reeb, Andrew Young and so many others. This poem from 1919 took on new meaning for them as they marched in the 1960’s. It continues to inspire those who struggle for justice today.

If we must die, let it not be like hogs

Hunted and penned in an inglorious spot,

While round us bark the mad and hungry dogs,

Making their mock at our accursèd lot.

If we must die, O let us nobly die,

So that our precious blood may not be shed

In vain; then even the monsters we defy

Shall be constrained to honor us though dead!

O kinsmen! we must meet the common foe!

Though far outnumbered let us show us brave,

And for their thousand blows deal one death-blow!

What though before us lies the open grave?

Like men we’ll face the murderous, cowardly pack,

Pressed to the wall, dying, but fighting back!

Benediction by John Lewis

The following words are taken from a longer “final essay” written by John Lewis shortly before he died.

Though I may not be here with you, I urge you

to answer the highest calling of your heart

and stand up for what you truly believe.

In my life I have done all I can to demonstrate that the way of peace,

the way of love and nonviolence,

is the more excellent way.

Now it is your turn to let freedom ring.

When historians pick up their pens to write the story of the 21st century,

let them say that it was your generation

who laid down the heavy burdens of hate at last

and that peace finally triumphed over violence, aggression and war.

So I say to you,

walk with the wind, brothers and sisters.

Let the spirit of peace and the power of everlasting love be your guide.

Sermon by Budd Friend-Jones

August 2, 2020

This morning I want us to remember and honor three great individuals in our nation’s recent history. To paraphrase the Herald-Tribune, they were among the Founding Fathers and Founding Mothers of a Better America. They invested their lives in overcoming racism and other oppressions in America. All three were ordained ministers. All three worked at the center of the Civil Rights Movement from the 1950’s down to the present time. All three received our nation’s highest honor, the national Medal of Freedom.

On March 27, the Reverend Joseph Echols Lowery passed away at age 98. He was followed in death by the Reverend C. T. Vivian on July 17, and by Congressman John Lewis the very next day.

Joseph Lowery is often called the Dean of the Civil Rights movement. He founded the Southern Christian Leadership Conference with Martin Luther King Jr. He helped lead the Montgomery bus boycott and headed the Alabama Civic Affairs Association, an organization devoted to the desegregation of buses and public places. He was a co-founder and president of the Black Leadership.

He protested the existence of Apartheid in South Africa and was one of the first five black men arrest outside the South African embassy in Washington, DC. He was a strong advocate for LGBTQ rights, including equality in marriage.

C. T. Vivian helped to organize the first sit-ins in Nashville in 1960 and the first civil rights march in 1961. He participated in Freedom Rides. He worked alongside Martin Luther King Jr. as the national director of affiliates for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. He led sit-ins at lunch counters, boycotts of businesses, and marches that continued for weeks or months in segregated cities. He was arrested often, jailed and beaten. At the end of a violence-plagued interracial Freedom Ride to Jackson, he was dispatched to the Hinds County Prison Farm, where he was beaten by guards. In 1964, he was nearly killed in St. Augustine, Florida, and once, on an Atlantic beach, roving white gangs whipped Black bathers with chains and almost drowned C.T. Vivian. Yet he always kept the focus of the struggle in a moral and spiritual context. He later wrote, “It was on this plane that the movement first confronted the conscience of the nation.” Fellow civil rights activists knew him as the “resident theologian” in King’s inner circle, Rev. Jesse Jackson recalled.

Until his death he was a fervent believer in Non-violence. He always instructed protesters, “Nonviolence is the only honorable way of dealing with social change, because if we are wrong, nobody gets hurt but us.”

And finally, of course, there is John Robert Lewis. So much has been said about him in the last few days, and deservedly so, but I hesitate to another word. From the days of his youth he was involved in peaceful protest and civil rights. He was one of the first Freedom Riders, beaten nearly to death, an organizer and speaker at the March on Washington, an organizer of the Selma to Montgomery march, and so much more. The son of sharecroppers in Alabama, he rose to the heights of power as a member of the US House of Representatives for 33 years. He has been called an “arc-bender”. He believed that the learning that matters most involves moral edification. History will remember him as one of the most respected moral and political leaders in our history.

All three have been called “Icons” of the Civil Rights Movement. I believe they were icons of something even larger. An Icon, in the classical religious sense, is a window into a higher realm.

These men, along with many others, were windows into the very best of human nature. In them we see integrity, courage, selflessness and a higher moral purpose. Through them we can glimpse what we also can be.

All three were co-workers with the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. All three were deeply immersed in the ethical and spiritual teachings of Jesus of Nazareth from the time they were children. All three also learned and practiced the spiritual disciplines of satyagraha and non-violence as articulated by Mohandas Gandhi and taught by James Lawson and re-enforced by Dr. King.

Satyagraha means “truth force”. It is the power that comes from living and acting in the Truth. It is the power of absolute integrity.

Non-violence is a way of life based on a profound love ethic, a love toward the other, no matter how egregious or hurtful their behavior is toward us.

Satyagraha leads toward greater justice. Non-violence leads toward the Beloved Community. These men never abandoned this philosophy.

For example, in the following clip, C. T. Vivian is speaking about the bombing of the Black church in Birmingham, Alabama, and the deaths of four little girls who were killed when the bomb detonated.

Watch C. T. Vivian on Bombing of Birmingham Church

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Rea1ftD5ePU

(Begin at 2:09 minutes in)

The true genius of the civil rights movement was its spiritual intentionality and inclusivity. It was never the Black race against the White race. As Vivian said, “What more can we do in freeing up not only African Americans but of (all) people in this nation? It’s not only a matter of freeing Black people, but of freeing White people as well. We really can’t free one without freeing the other.” He knew that we are all bound together as Dr. King said, in an “inescapable web of mutuality.” No one can truly be free from oppression until all of us are free together.

All of them knew they were involved in a great spiritual struggle. In 2004, John Lewis explained to PBS: “In my estimation, the civil rights movement was a religious phenomenon. When we’d go out to sit in or go out to march, I felt, and I really believe, there was a force in front of us and a force behind us, ’cause sometimes you didn’t know what to do. You didn’t know what to say, you didn’t know how you were going to make it through the day or through the night. But somehow and some way, you believed – you had faith – that it all was going to be all right.”

Watch John Lewis at Selma

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vumOmpv-L6A

Lewis constantly reminded us of the work still to be done to “redeem the soul of America”. “Don’t get lost in a sea of despair….,” he cautioned at the Edmund Pettis Bridge, and who should know better about that? Echoing both Vivian and King, he proclaimed, “We are one family, the human family. We all live in the same house, the American house…”

America is at a moral as well as a political and constitutional tipping point.

Black Lives Matter, said Melina Abdullah, its co-founder in Las Angeles, is much more than a movement for racial and social justice movement. At its core, she said, it is a spiritual movement.

Historian John Meacham has consistently observed that our present crisis is about the theology of America. Are we devoted to the words, “Thou shalt love thy neighbor as thyself”? Or are we devoted to the selfish pursuit of our own happiness, others be damned? The struggle is about the content of our character.

Watch Civil Rights Leader Rev. Joseph Lowery: 'We Ain't Going Back'

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TuPu5-cnF2Q

Let us rise up from the basement of race and color. Let us rise to the higher ground of the content of character….

The higher ground of character…

“Well, we ain’t goin’ back. We ain’t goin’ back. We’ve come to far, marched too long, prayed too hard, wept too bitterly, bled too profusely, and died too young to let anybody turn back the clock on our journey to justice.”

Let all the people say, Amen!

Reading “If we must die” by Claude McKay

During the summer of 1919, our country was struggling with two watershed moments. For a year-and-a-half the world had been engulfed by a devastating pandemic called the “Spanish Flu”; it would continue to infect communities for another year. In addition, the so-called Great War had just ended. Over five million soldiers were returning from abroad. They were seeking jobs that did not exist.

380,000 of those were African American. They too had borne the sacrifices of warfare for their country. They too expected its rights and benefits. W. E. B. Dubois, among others, urged them to continue their fight for democracy at home. But sadly, there were lynchings, church burnings and rampant anti-Black violence across the country.

This became known as “Red Summer”. Historians estimate that a thousand or more African Americans were killed before the violence subsided. Our country was caught in the clash of hope and threat, Time Magazine reported, between new dreams and entangled fears. This is the context for the poem you’re about to hear.

“If we must die” was written by Claude McKay, a central figure of the Harlem Renaissance. Jamaica-born, McKay was a novelist and poet of African descent. He blended his African pride with his love for British poetry. This is one of his most famous poems. He wrote it in the form of a Shakespearean sonnet. It speaks to the desperation felt among African Americans everywhere during “Red Summer”.

C. T. Vivian of blessed memory is the reader here. He was one of the primary architects of the non-violent civil rights movement that also gave us Dr. King, John Lewis, Joseph Lowery, James Reeb, Andrew Young and so many others. This poem from 1919 took on new meaning for them as they marched in the 1960’s. It continues to inspire those who struggle for justice today.

If we must die, let it not be like hogs

Hunted and penned in an inglorious spot,

While round us bark the mad and hungry dogs,

Making their mock at our accursèd lot.

If we must die, O let us nobly die,

So that our precious blood may not be shed

In vain; then even the monsters we defy

Shall be constrained to honor us though dead!

O kinsmen! we must meet the common foe!

Though far outnumbered let us show us brave,

And for their thousand blows deal one death-blow!

What though before us lies the open grave?

Like men we’ll face the murderous, cowardly pack,

Pressed to the wall, dying, but fighting back!

Benediction by John Lewis

The following words are taken from a longer “final essay” written by John Lewis shortly before he died.

Though I may not be here with you, I urge you

to answer the highest calling of your heart

and stand up for what you truly believe.

In my life I have done all I can to demonstrate that the way of peace,

the way of love and nonviolence,

is the more excellent way.

Now it is your turn to let freedom ring.

When historians pick up their pens to write the story of the 21st century,

let them say that it was your generation

who laid down the heavy burdens of hate at last

and that peace finally triumphed over violence, aggression and war.

So I say to you,

walk with the wind, brothers and sisters.

Let the spirit of peace and the power of everlasting love be your guide.

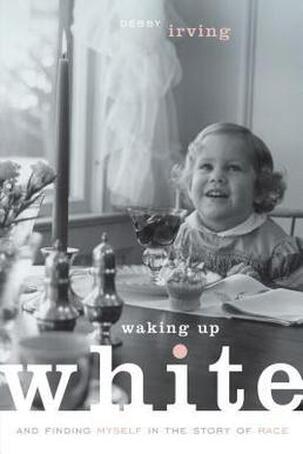

What Wasn't Said:

Lessons my mother couldn’t teach me.

Excerpt from the book, Waking up White by Debby Irving.

“WHATEVER HAPPENED TO ALL THE INDIANS?” I asked my mother on a Friday morning ride home from the library. I was five years old.

The library’s main draw for me had always been a large, colorful mural located high on the lobby wall. It featured three feathered and fringed Indians standing with four colonial men on a lush, green lakeshore. The colonists didn’t hold much interest, perhaps because these were images familiar to me, a white New England girl with colonial ancestors. The dark-skinned Indians and their “exotic” dress, on the other hand, took my breath away.

Lying on my bedroom floor back at home, I had pored over the images from a book on Indian life. Colorful illustrations of teepees clustered close together, horses being ridden bareback, and food being cooked over the campfire added to my romanticized imaginings of the Indian life. Children and grown-ups appeared to live in an intergenerational world in which boundaries between work and play blurred.

Eventually, my infatuation led to curiosity. If I had descended from colonists, there must be kids who’d descended from Indians, right? I wondered if there was a place I could go meet them, which is what led me that Friday morning to ask the simple question, “Whatever happened to all the Indians?”

“Oh, those poor Indians,” my mother said, sagging a little as she shook her head with something that looked like sadness.

“Why? What happened?” I turned in my seat, alarmed.

“They drank too much,” she answered. My heart sank. “They were lovely people,” she said, “who became dangerous when they drank liquor.”

I could not believe what I was hearing. Dangerous? This would have been the last word I would have applied to my horseback-riding, nature-loving friends.

“Dangerous from drinking?” I asked.

“Yes, it’s so sad. They just couldn’t handle it, and it ruined them really.”

This made no sense to me. My parents drank liquor. Some friends and family drank quite a bit actually. How could something like liquor bring down an entire people? People who loved grass and trees and lakes and horses, the stuff I love?

My mother went on to tell a tale in vivid detail about children hiding under a staircase, in pitch blackness, trying to escape the ravages of their local friendly Indian now on a drunken rampage, ax in hand. They were all murdered.

“Well, what happened to the Indian?” I asked, my heart beating in my chest.

She paused, thinking. “You know, I don’t know,” my mother answered sincerely.

I never questioned this narrative’s truth or fullness despite its dissonance with the peaceful images in my books. My mother was warm, compassionate, and bright. She told me the versions of events as she knew them, errors and omissions included. Just as she had once done, I used my scant information to construct a story about humanity. Over the course of my childhood the media confirmed my idea of Indians as “savage” and “dangerous.” I came to see them as drunks who grunted, whooped, yelled, and painted their faces to scare and scalp white people. What a tragedy that over time my natural curiosity, open mind, and loving heart dulled, keeping me from confronting wrongs I never knew existed.

Lessons my mother couldn’t teach me.

Excerpt from the book, Waking up White by Debby Irving.

“WHATEVER HAPPENED TO ALL THE INDIANS?” I asked my mother on a Friday morning ride home from the library. I was five years old.

The library’s main draw for me had always been a large, colorful mural located high on the lobby wall. It featured three feathered and fringed Indians standing with four colonial men on a lush, green lakeshore. The colonists didn’t hold much interest, perhaps because these were images familiar to me, a white New England girl with colonial ancestors. The dark-skinned Indians and their “exotic” dress, on the other hand, took my breath away.

Lying on my bedroom floor back at home, I had pored over the images from a book on Indian life. Colorful illustrations of teepees clustered close together, horses being ridden bareback, and food being cooked over the campfire added to my romanticized imaginings of the Indian life. Children and grown-ups appeared to live in an intergenerational world in which boundaries between work and play blurred.

Eventually, my infatuation led to curiosity. If I had descended from colonists, there must be kids who’d descended from Indians, right? I wondered if there was a place I could go meet them, which is what led me that Friday morning to ask the simple question, “Whatever happened to all the Indians?”

“Oh, those poor Indians,” my mother said, sagging a little as she shook her head with something that looked like sadness.

“Why? What happened?” I turned in my seat, alarmed.

“They drank too much,” she answered. My heart sank. “They were lovely people,” she said, “who became dangerous when they drank liquor.”

I could not believe what I was hearing. Dangerous? This would have been the last word I would have applied to my horseback-riding, nature-loving friends.

“Dangerous from drinking?” I asked.

“Yes, it’s so sad. They just couldn’t handle it, and it ruined them really.”

This made no sense to me. My parents drank liquor. Some friends and family drank quite a bit actually. How could something like liquor bring down an entire people? People who loved grass and trees and lakes and horses, the stuff I love?

My mother went on to tell a tale in vivid detail about children hiding under a staircase, in pitch blackness, trying to escape the ravages of their local friendly Indian now on a drunken rampage, ax in hand. They were all murdered.

“Well, what happened to the Indian?” I asked, my heart beating in my chest.

She paused, thinking. “You know, I don’t know,” my mother answered sincerely.

I never questioned this narrative’s truth or fullness despite its dissonance with the peaceful images in my books. My mother was warm, compassionate, and bright. She told me the versions of events as she knew them, errors and omissions included. Just as she had once done, I used my scant information to construct a story about humanity. Over the course of my childhood the media confirmed my idea of Indians as “savage” and “dangerous.” I came to see them as drunks who grunted, whooped, yelled, and painted their faces to scare and scalp white people. What a tragedy that over time my natural curiosity, open mind, and loving heart dulled, keeping me from confronting wrongs I never knew existed.

Catherine Bonner

Catherine Bonner

Talking to Strangers

Sermon by Catherine Bonner

Last year I gave a sermon on Don’t Label Me based on the book of the same name by Irshad Manji. In that sermon I discussed how it is our default to categorize and label people and in doing so we stop looking at the humanity of each individual. By labelling each other, it is easy to shame, blame and game groups of people. I encouraged you to reach out to those who do not look or think like you to start a conversation with them where you listened more than talked with an open heart and open mind to find common ground.

So now that you have talked with Strangers….

What? You aren’t talking with strangers?

Ok, I get that we are in a Pandemic right now but hang in there with me because this sermon is about talking to strangers AND trying to discern truth and there is a big finale at the end you won’t want to miss!

DON’T TALK TO STRANGERS! This is the kind of instruction you get at a very young age and it doesn’t usually come with much explanation. It’s just one of those universal truths that we seem to accept as law for all human beings. But why? Typical parental responses include: “We have to keep our children safe.” “Strangers are dangerous.” “Children are too trusting.”

While well-meaning, in teaching our children about “Stranger Danger” we are planting a culture of fear and distrust of “others”. Children often freeze when a neighbor walks down the sidewalk, or they refuse to talk. Out of parental fear, children no longer play like many of us did roaming the neighborhood in packs until dusk and dinner time. More restricted play limits a child’s ability to learn how to work-out problems, how to trust their own gut instincts on what is good and bad and how to stand up for themselves.

But the world is a scary place! That is true for children and adults but at some point in our life we have to learn to talk to strangers

But why is it so hard to talk to strangers? Is it just the embedded culture of fear? Is it that capitalism has trained us to sit in front of a screen being a consumer rather than being social with our neighbors? Is it that talking to a stranger makes us uncomfortable because we don’t know what they think or how they will respond to us? Will talking to them challenge your beliefs and ideals, two of the most important things you possess? It is comfortable only interacting with those we know or where we have anonymity.

But at one point, everyone you are comfortable with was a stranger; someone unknown to you. So what do we do to make sense of people we don’t know? In Malcolm Gladwell’s book, Talking to Strangers, he explores our “defaults” and how those tools and strategies do not always give us the right answer. He poses two puzzling questions: Why can’t we tell when the stranger in front of us is lying and how is it that meeting a stranger can sometimes make us worse at making sense of that person than NOT meeting them?

So let’s cover a few terms before going on. Truth Default Theory (TDT for short) is a relatively new theory put out by Timothy R. Levine, a professor and chair of communication studies at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. The basic idea of TDT is that when we communicate with other people, we not only tend to believe them, but the thought that maybe we shouldn’t does not even come to mind. This is a good thing for two reasons.

First, and most important, the truth-default is needed for communication to function. Just image what would happen to our social constructs if we did not believe anything that someone said or communicated to us. You know those people. The ones who are always skeptical about EVERYTHING? The clinical term that we all use for those individuals is paranoia. Second, most people are mostly honest most of the time. BUT, the truth-default does makes us vulnerable to deception.

“Transparency is the idea that people’s behavior and demeanor—the way they represent themselves on the outside—provides an authentic and reliable window into the way they feel on the inside. It is the second of the crucial tools we use to make sense of strangers. When we don’t know someone, or can’t communicate with them, or don’t have the time to understand them properly, we believe we can make sense of them through their behavior and demeanor.” This is how we have all been trained. He or she is lying if they avoid your gaze or are nervous, or sweat profusely. This person is a psychopath and must be guilty if they show no emotion or react coldly or out of context for a situation. Isn’t that what we see on the media? Malcolm Gladwell uses the term “mismatched” when a person’s demeanor and “cues” don’t meet the predetermined social norms

So back to Malcolm’s questions. Why can’t we tell when the stranger in front of us is lying? While many of us are not talking directly with strangers now the same question holds true for discerning misinformation, conspiracy theories, hoaxes, and scams on the Internet. In a famous experiment by Stanley Milgram in 1961 participants were “fooled” to think they were giving ever increasing shocks to “learners” for giving wrong answers. Here are the results of the experiment.

I fully believed the learner was getting painful shocks. 56.1%

Although I had some doubts, I believed the learner was probably getting the shocks. 24%

I just wasn’t sure whether the learner was getting the shocks or not. 6.1%

Although I had some doubts, I thought the learner was probably not getting the shocks 11.4%

I was certain the learner was not getting the shocks 2.4%

Remarkably, over 40% questioned the validity of the experiment but their doubts were just not enough to trigger them out of truth-default. This is Levine’s point. You believe someone not because you have no doubts about them but because you don’t have enough doubts about them. I imagine that each of us can think of a time where we believed something even when we had doubts.

How is it that meeting a stranger can sometimes make us worse at making sense of that person than NOT meeting them?

Evolutionarily, we have used transparency to judge strangers as a prelude to either the flight or fight response. So after so many millennia, why are we so bad at it? Like the TDT, most people’s behaviors and demeanors “match” the context of the situation but there are many “mismatched” people that throw us the curve. In Malcolm’s book, he uses the example of a judge who hears many bail cases daily. It is the judge’s habit to do a quick review of the case file, have the defendant appear before them and ask them questions. The judge is trying to glean from visual clues and the info in the file whether this person will commit another crime while out on bail. A study showed that a computer algorithm using only the data in the case file was much better able to predict those that would not commit a crime while out on bail versus the judge who is trying to “read” the situation. And there are many many more historical examples of where the visual clues did not “match” and decisions based on these false clues ended up disastrously.

Multiple studies show that people’s ability to detect lies is only slightly better than flipping a coin including those that have training in lie detecting! But what of those individuals whose job it is to talk to strangers and detect lies/truth every day? That would include our public safety, emergency medical personnel, and our justice and law enforcement personnel. For today though, I want to focus on our law enforcement personnel, society’s front line.

As I have personally journeyed down the path of becoming racially “woke”, I too echoed the cluelessness of Debby Irving in our early reading. I am a good person, racially aware, don’t see color, provide opportunities for people of color to become more “white” and over time my natural curiosity, open mind, and loving heart dulled, keeping me from confronting wrongs I never knew existed. When talking with my own children on “Stranger Danger” I always told them to be aware of their surroundings, to talk to strangers but be skeptical of motive, to use their gut instinct and find a person of authority such as the police if they needed help. Never did I imagine that people of color had a different talk with their children and that it happens almost daily. Never did I worry that my children might not come home nor did my children ever worry I might not come home. I would like to share with you a short video clip on what these conversations entail. (See below for the complete video)

That was just a piece of the video put together by The Cut on “The Talk.”

In Malcolm Gladwell’s book he uses the case of Sandra Bland, the black woman stopped in Texas in 2015 for not signaling a lane change as an example of why we fail disastrously when we use transparency to understand “mismatched” people. In this case with the death of Ms. Bland in the jail three days later.

As one of the parents in the video remarked, all the law enforcement officers were people first bringing their own biases, thoughts, and backgrounds to the job. This is true whether a person goes into the field because of a passion to protect and serve everyone, or a passion to protect the current system of white superiority as the status quo or simply for the power the role has. The system of white superiority has indoctrinated ALL of us whether directly in the case of out-right bigotry or more often subtly by the way we are taught our history or treat others differently because of the color of their skin or their culture. This indoctrination and constant gaslighting by our leaders that “racism” is no longer an issue since . . . .(you can fill in the blank although my favorite one is “we elected a black president”). This is a false narrative but many of us seem to believe it. Due to this gaslighting, too many well-minded “good” people feel that any attack on society’s systems by people of color is now a call to extinguish the white way of life and the white race which too is a false narrative. Even those who are outraged by the death of George Floyd still harbor doubts about the extent of racism because we have become comfortable with “not seeing”.

So what happened in the case of Sandra Bland? How did this encounter become so disastrous? Over the past 30 years we have trained our law enforcement to be more “militant” under the guise of the war on drugs. The Fourth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution protects citizens from “unreasonable searches and seizures.” That’s why the police cannot search your home without a warrant or a police officer must have a “reasonable suspicion” to stop and frisk you. But if you’re in your car, the bar to meet that standard is very low because traffic codes in the U.S. give law enforcement literally hundreds of reasons to stop a motorist. Legal scholar David Harris writes, “And then there are catch-all provisions: rules that allow police to stop drivers for conduct that complies with all the rules on the books, but that officers consider “imprudent” or “unreasonable” under the circumstances, or that describe the offense in language so broad as to make a violation virtually coextensive with the officer’s unreviewable personal judgment.” And our courts have supported the officer’s power to make those decisions even if those decisions are wrong and have caused harm.

Officer Encinia who stopped Sandra Bland made routine traffic stops, indiscriminate of race, as the pretext to look for other illegal activity. He had gone through the standard police training. What was unusual was that he only used transparency to judge the guilt of a person and did not default to truth making him more paranoid about Ms. Bland’s “mismatched” reactions to the situation and convincing him from the start that she was guilty of something. Standard police training does include de-escalation techniques and bias training but clearly not enough since law enforcement officers repeatedly allow their personal bias and egos to override the training on de-escalation. The encounter between Officer Encinia and Ms Bland escalated out of control because she lit a cigarette to calm her nerves and refused to comply with his order to put out the cigarette which the officer legally cannot order. The confrontation ended up with Ms. Bland being literally dragged from the car, thrown to the ground, threatened with tazing, handcuffed and charged with third degree felony for assaulting the officer while resisting arrest. The back story that creates the mismatch in Ms. Bland’s demeanor includes a history of depression and suicide attempts and trauma from similar stops in Chicago where she was moving from to start a new life in Texas. In the three days she spent in jail before taking her own life, Sandra Bland was distraught, weeping constantly, making phone call after phone call. She was in crisis, yet, no one in the criminal justice department recognized the signs or did anything about it.

In the backlash to the death of George Floyd, there are cries to “Defund the Police” which is confused by many to mean eradicate all policing. During a workshop I recently attended, a black man stated that we NEED a police force to stop crimes especially hate crimes. But most of law enforcement calls today are not about crimes and fall into the category of domestic disputes and traffic violations. Social workers, behavior therapists and psychologists are trained hours and hours to learn how to recognize, understand, and help individuals that are in crisis (ie how to Talk to Strangers) by using context and coupling of visual clues which are much more reliable. Law Enforcement officers do NOT get that level of training. They are trained hours and hours on how to properly use and discharge weapons and often do not get that right.

For most, Defund the Police, is a call to rethink how we police, how we can redeploy the large law enforcement budgets to hiring social workers and those trained in helping people in crisis, and how law enforcement and social workers can partner together to reduce the amount of police violence, mass incarceration, and systemic racism in our policing and justice programs. Defund the Police will take all of us, and especially whites, to step up and partner with people of color, indigenous peoples and other marginalized groups to reform our systems. I encourage you to join our Social Justice Committee that meets monthly to see how you can become engaged in this fight. Check out our new Racial Justice pages that are being formed and shaped daily for additional information on education and activities you can participate in.

Sermon by Catherine Bonner

Last year I gave a sermon on Don’t Label Me based on the book of the same name by Irshad Manji. In that sermon I discussed how it is our default to categorize and label people and in doing so we stop looking at the humanity of each individual. By labelling each other, it is easy to shame, blame and game groups of people. I encouraged you to reach out to those who do not look or think like you to start a conversation with them where you listened more than talked with an open heart and open mind to find common ground.

So now that you have talked with Strangers….

What? You aren’t talking with strangers?

Ok, I get that we are in a Pandemic right now but hang in there with me because this sermon is about talking to strangers AND trying to discern truth and there is a big finale at the end you won’t want to miss!

DON’T TALK TO STRANGERS! This is the kind of instruction you get at a very young age and it doesn’t usually come with much explanation. It’s just one of those universal truths that we seem to accept as law for all human beings. But why? Typical parental responses include: “We have to keep our children safe.” “Strangers are dangerous.” “Children are too trusting.”

While well-meaning, in teaching our children about “Stranger Danger” we are planting a culture of fear and distrust of “others”. Children often freeze when a neighbor walks down the sidewalk, or they refuse to talk. Out of parental fear, children no longer play like many of us did roaming the neighborhood in packs until dusk and dinner time. More restricted play limits a child’s ability to learn how to work-out problems, how to trust their own gut instincts on what is good and bad and how to stand up for themselves.

But the world is a scary place! That is true for children and adults but at some point in our life we have to learn to talk to strangers

But why is it so hard to talk to strangers? Is it just the embedded culture of fear? Is it that capitalism has trained us to sit in front of a screen being a consumer rather than being social with our neighbors? Is it that talking to a stranger makes us uncomfortable because we don’t know what they think or how they will respond to us? Will talking to them challenge your beliefs and ideals, two of the most important things you possess? It is comfortable only interacting with those we know or where we have anonymity.

But at one point, everyone you are comfortable with was a stranger; someone unknown to you. So what do we do to make sense of people we don’t know? In Malcolm Gladwell’s book, Talking to Strangers, he explores our “defaults” and how those tools and strategies do not always give us the right answer. He poses two puzzling questions: Why can’t we tell when the stranger in front of us is lying and how is it that meeting a stranger can sometimes make us worse at making sense of that person than NOT meeting them?

So let’s cover a few terms before going on. Truth Default Theory (TDT for short) is a relatively new theory put out by Timothy R. Levine, a professor and chair of communication studies at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. The basic idea of TDT is that when we communicate with other people, we not only tend to believe them, but the thought that maybe we shouldn’t does not even come to mind. This is a good thing for two reasons.

First, and most important, the truth-default is needed for communication to function. Just image what would happen to our social constructs if we did not believe anything that someone said or communicated to us. You know those people. The ones who are always skeptical about EVERYTHING? The clinical term that we all use for those individuals is paranoia. Second, most people are mostly honest most of the time. BUT, the truth-default does makes us vulnerable to deception.

“Transparency is the idea that people’s behavior and demeanor—the way they represent themselves on the outside—provides an authentic and reliable window into the way they feel on the inside. It is the second of the crucial tools we use to make sense of strangers. When we don’t know someone, or can’t communicate with them, or don’t have the time to understand them properly, we believe we can make sense of them through their behavior and demeanor.” This is how we have all been trained. He or she is lying if they avoid your gaze or are nervous, or sweat profusely. This person is a psychopath and must be guilty if they show no emotion or react coldly or out of context for a situation. Isn’t that what we see on the media? Malcolm Gladwell uses the term “mismatched” when a person’s demeanor and “cues” don’t meet the predetermined social norms

So back to Malcolm’s questions. Why can’t we tell when the stranger in front of us is lying? While many of us are not talking directly with strangers now the same question holds true for discerning misinformation, conspiracy theories, hoaxes, and scams on the Internet. In a famous experiment by Stanley Milgram in 1961 participants were “fooled” to think they were giving ever increasing shocks to “learners” for giving wrong answers. Here are the results of the experiment.

I fully believed the learner was getting painful shocks. 56.1%

Although I had some doubts, I believed the learner was probably getting the shocks. 24%

I just wasn’t sure whether the learner was getting the shocks or not. 6.1%

Although I had some doubts, I thought the learner was probably not getting the shocks 11.4%

I was certain the learner was not getting the shocks 2.4%

Remarkably, over 40% questioned the validity of the experiment but their doubts were just not enough to trigger them out of truth-default. This is Levine’s point. You believe someone not because you have no doubts about them but because you don’t have enough doubts about them. I imagine that each of us can think of a time where we believed something even when we had doubts.

How is it that meeting a stranger can sometimes make us worse at making sense of that person than NOT meeting them?

Evolutionarily, we have used transparency to judge strangers as a prelude to either the flight or fight response. So after so many millennia, why are we so bad at it? Like the TDT, most people’s behaviors and demeanors “match” the context of the situation but there are many “mismatched” people that throw us the curve. In Malcolm’s book, he uses the example of a judge who hears many bail cases daily. It is the judge’s habit to do a quick review of the case file, have the defendant appear before them and ask them questions. The judge is trying to glean from visual clues and the info in the file whether this person will commit another crime while out on bail. A study showed that a computer algorithm using only the data in the case file was much better able to predict those that would not commit a crime while out on bail versus the judge who is trying to “read” the situation. And there are many many more historical examples of where the visual clues did not “match” and decisions based on these false clues ended up disastrously.

Multiple studies show that people’s ability to detect lies is only slightly better than flipping a coin including those that have training in lie detecting! But what of those individuals whose job it is to talk to strangers and detect lies/truth every day? That would include our public safety, emergency medical personnel, and our justice and law enforcement personnel. For today though, I want to focus on our law enforcement personnel, society’s front line.

As I have personally journeyed down the path of becoming racially “woke”, I too echoed the cluelessness of Debby Irving in our early reading. I am a good person, racially aware, don’t see color, provide opportunities for people of color to become more “white” and over time my natural curiosity, open mind, and loving heart dulled, keeping me from confronting wrongs I never knew existed. When talking with my own children on “Stranger Danger” I always told them to be aware of their surroundings, to talk to strangers but be skeptical of motive, to use their gut instinct and find a person of authority such as the police if they needed help. Never did I imagine that people of color had a different talk with their children and that it happens almost daily. Never did I worry that my children might not come home nor did my children ever worry I might not come home. I would like to share with you a short video clip on what these conversations entail. (See below for the complete video)

That was just a piece of the video put together by The Cut on “The Talk.”

In Malcolm Gladwell’s book he uses the case of Sandra Bland, the black woman stopped in Texas in 2015 for not signaling a lane change as an example of why we fail disastrously when we use transparency to understand “mismatched” people. In this case with the death of Ms. Bland in the jail three days later.

As one of the parents in the video remarked, all the law enforcement officers were people first bringing their own biases, thoughts, and backgrounds to the job. This is true whether a person goes into the field because of a passion to protect and serve everyone, or a passion to protect the current system of white superiority as the status quo or simply for the power the role has. The system of white superiority has indoctrinated ALL of us whether directly in the case of out-right bigotry or more often subtly by the way we are taught our history or treat others differently because of the color of their skin or their culture. This indoctrination and constant gaslighting by our leaders that “racism” is no longer an issue since . . . .(you can fill in the blank although my favorite one is “we elected a black president”). This is a false narrative but many of us seem to believe it. Due to this gaslighting, too many well-minded “good” people feel that any attack on society’s systems by people of color is now a call to extinguish the white way of life and the white race which too is a false narrative. Even those who are outraged by the death of George Floyd still harbor doubts about the extent of racism because we have become comfortable with “not seeing”.

So what happened in the case of Sandra Bland? How did this encounter become so disastrous? Over the past 30 years we have trained our law enforcement to be more “militant” under the guise of the war on drugs. The Fourth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution protects citizens from “unreasonable searches and seizures.” That’s why the police cannot search your home without a warrant or a police officer must have a “reasonable suspicion” to stop and frisk you. But if you’re in your car, the bar to meet that standard is very low because traffic codes in the U.S. give law enforcement literally hundreds of reasons to stop a motorist. Legal scholar David Harris writes, “And then there are catch-all provisions: rules that allow police to stop drivers for conduct that complies with all the rules on the books, but that officers consider “imprudent” or “unreasonable” under the circumstances, or that describe the offense in language so broad as to make a violation virtually coextensive with the officer’s unreviewable personal judgment.” And our courts have supported the officer’s power to make those decisions even if those decisions are wrong and have caused harm.

Officer Encinia who stopped Sandra Bland made routine traffic stops, indiscriminate of race, as the pretext to look for other illegal activity. He had gone through the standard police training. What was unusual was that he only used transparency to judge the guilt of a person and did not default to truth making him more paranoid about Ms. Bland’s “mismatched” reactions to the situation and convincing him from the start that she was guilty of something. Standard police training does include de-escalation techniques and bias training but clearly not enough since law enforcement officers repeatedly allow their personal bias and egos to override the training on de-escalation. The encounter between Officer Encinia and Ms Bland escalated out of control because she lit a cigarette to calm her nerves and refused to comply with his order to put out the cigarette which the officer legally cannot order. The confrontation ended up with Ms. Bland being literally dragged from the car, thrown to the ground, threatened with tazing, handcuffed and charged with third degree felony for assaulting the officer while resisting arrest. The back story that creates the mismatch in Ms. Bland’s demeanor includes a history of depression and suicide attempts and trauma from similar stops in Chicago where she was moving from to start a new life in Texas. In the three days she spent in jail before taking her own life, Sandra Bland was distraught, weeping constantly, making phone call after phone call. She was in crisis, yet, no one in the criminal justice department recognized the signs or did anything about it.

In the backlash to the death of George Floyd, there are cries to “Defund the Police” which is confused by many to mean eradicate all policing. During a workshop I recently attended, a black man stated that we NEED a police force to stop crimes especially hate crimes. But most of law enforcement calls today are not about crimes and fall into the category of domestic disputes and traffic violations. Social workers, behavior therapists and psychologists are trained hours and hours to learn how to recognize, understand, and help individuals that are in crisis (ie how to Talk to Strangers) by using context and coupling of visual clues which are much more reliable. Law Enforcement officers do NOT get that level of training. They are trained hours and hours on how to properly use and discharge weapons and often do not get that right.

For most, Defund the Police, is a call to rethink how we police, how we can redeploy the large law enforcement budgets to hiring social workers and those trained in helping people in crisis, and how law enforcement and social workers can partner together to reduce the amount of police violence, mass incarceration, and systemic racism in our policing and justice programs. Defund the Police will take all of us, and especially whites, to step up and partner with people of color, indigenous peoples and other marginalized groups to reform our systems. I encourage you to join our Social Justice Committee that meets monthly to see how you can become engaged in this fight. Check out our new Racial Justice pages that are being formed and shaped daily for additional information on education and activities you can participate in.

Video referred to during sermon: Closing hymn:

|

|

|

Script for This Little Light of Mine service July 5, 2020